Crime depends on how you define it rather than the action itself, which is only criminal in terms of the definition. My crime may not be your crime. This is not simply a verbal sophistry. In a developing country like South Africa with massive differentials between rich and poor (we have the highest Gini Coefficient in the world) and a government under President Jacob Zuma which looted the public coffers and hollowed out the prosecutorial authority, notions of crime have developed extremely blurred edges and depend on where you stand in the social order. What happens after the pandemic recedes has much to do with how we went into it and the effect it has had on social formations throughout the national fabric, from state and corporate entities to street-corner gangs.

Before Covid-19 appeared, the South African economy was in trouble with almost zero growth rate. There were power-outs because the Eskom electricity authority was falling apart, the national airline was billions of rands in debt and wanting a bailout and the transport network was almost on its knees. All of them had been sucked dry by ‘tenderpreneur’ looting and bad management. As lockdown happened, the Moodies rating agency downgraded the rand to junk status. This was not the best way to go into a national lockdown that literally froze the economy.

All of this is what we will come out of lockdown and have to deal with. The government under Cyril Ramaposa is committed to clean up the government and rebuild the economy trashed by his successor, but he’s starting on such a low baseline that it’s not going to be easy and will take a long time. Will he manage to stop the looting of state and municipal coffers? Can he re-energize business? Can he rebuild popular trust in government? Coronavirus is what he didn’t need to happen – it’s timing couldn’t have been worse.

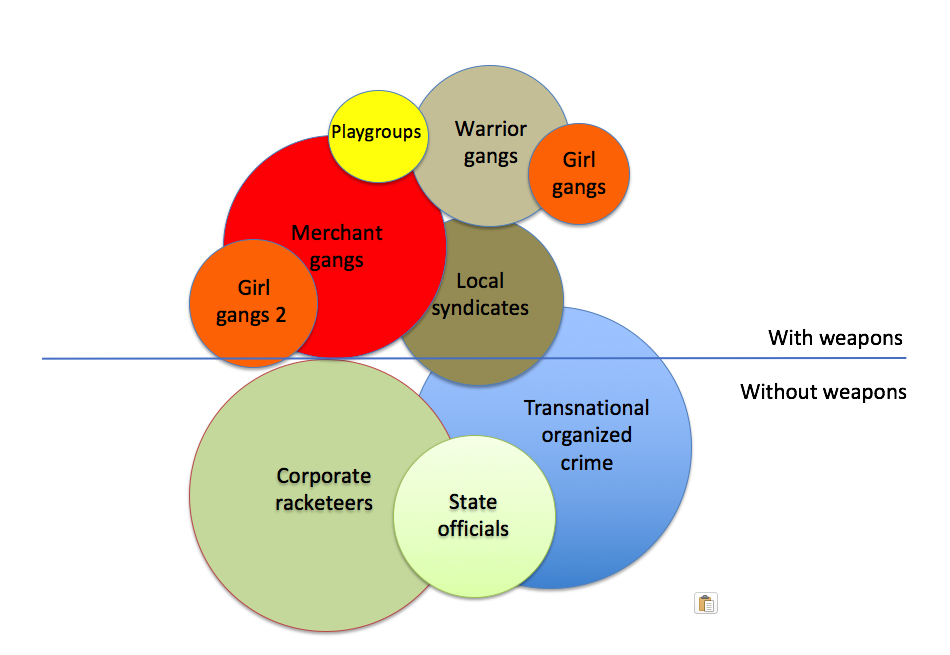

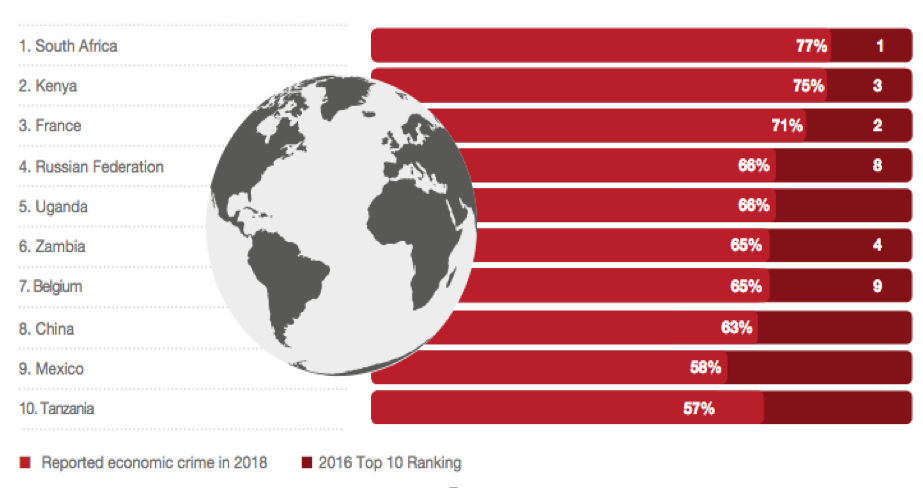

As a criminologist, it’s appropriate to ask where all this is heading in terms of the multiple avenues that crime will take as we emerge from the pandemic. In terms of what I have said above, it’s necessary to paint on a broad canvas, which looks something like this:

Another way to depict it is like this:

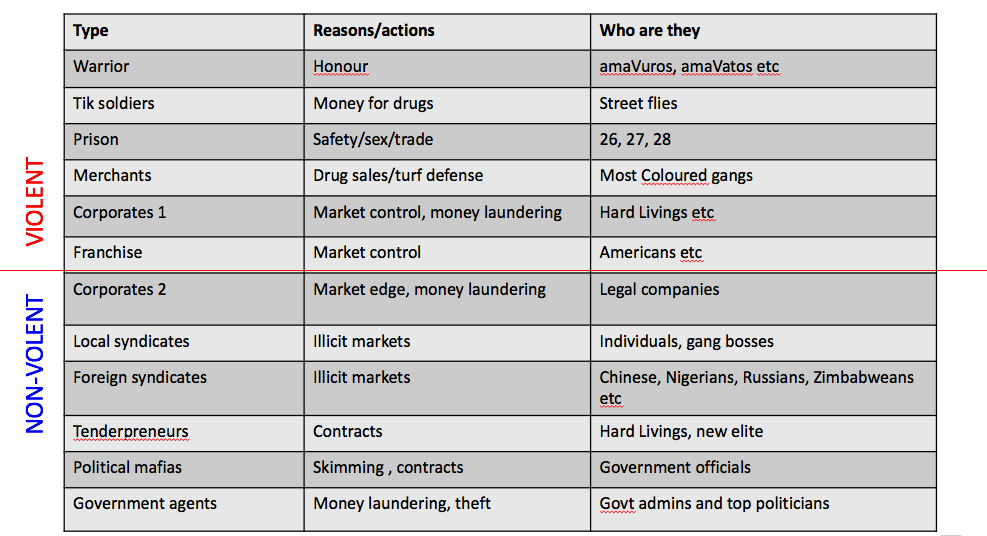

All the social formations above the central line are various forms of what would be conventionally defined as gangs and potentially violent, while the first three below the line would be considered related to the criminal market. The final three categories are what is conventionally termed white-collar crime and its impact in South Africa is considerable. Here’s a graph of the top 10 countries reporting economic crime:

There is no indication that any of these entities or illicit operations will change their tactics beyond the pandemic, though most will in some way have been distorted by it.

What has been considerably affected by lockdowns and the cessation of international travel, however, are illicit local and transnational trade routes –drugs and wildlife poaching being the hardest hit. Apart from cannabis, which is locally produced, almost all drugs such as heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine, and mandrax, originate on other continents. Supplies in South Africa are declining and there are as yet unconfirmed reports of gangs raiding and killing each other in ways that suggest they are running short of trade goods. After lockdowns end and international travel restarts, however, there’s no reason to hope that the drug trade will not resume as before.

With the wildlife poaching it’s another story. Smuggling of illegal wildlife in Southeast Asia hasn’t stopped but it’s slowing and traders are hurting. On February 1 China closed its borders and increased security is pinching off the flow of animal products.

As a result, in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Lao PDR along the Chinese border, traders eager to offload their growing stockpiles were offering deep discounts on wildlife goods. Many shut shop when the flow of tourists dried up and batches of raw ivory is reported to be bottle-necked in Cambodia.

According to the Wildlife Justice Commission (WJC), traffickers are becoming desperate as well-tested chains of bribery fall apart. Sudden and unpredictable aviation security measures such as last-minute flight diversions also had an unforeseen impact on criminal dynamics. Fear of lockdown clearly hampered movements. A trafficker told the WJC: ‘When you fly to another country they will quarantine you.’

Increased border security and curfews are leading to increased arrests. There were busts of rhino horn, ivory, and pangolin scales which were shipped before pandemic lockdowns and languished in ports long enough to be detected. Live pangolins, widely suspected as being the vector of Covid-19 from bats to humans, fell out of favor and became hard to sell after Beijing prevented the sale of wildlife in all wet markets and banned trade in wild animals for consumption.

Wildlife smuggling is demand-driven, so the effect of Asian lockdowns, bans, and arrests had a knock-on effect in African source countries. It also caused a shift from horns and tusks to meat.

In a few areas, conventional poaching increased during the lockdown, possibly to stockpile awaiting the reopening of transport routes. In the Northern Cape, poachers have been hitting game farm livestock. Rhino poaching was also taking place there. According to Nico Jacobs of Rhino 911, ‘poaching has ramped up significantly since the nationwide lockdown got underway, with poaching incidents in the Northern Cape allegedly taking place “every day”. Just as soon as the lockdown hit South Africa, we started having an incursion almost every single day,’ he said.

Beyond South Africa’s borders similar events were reported. Rhino Conservation Botswana founder, Map Ives, said poachers there had been emboldened because the playing field is in their favor and they didn’t have as many problems moving around. ‘They are professional and adept at running off with rhino horns in minutes and dodging security forces. They are masters at evading detection.’

Speaking about Mozambique, Vanda Felbab-Brown, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution in Washington, said the virus may wind up facilitating rather than stalling illegal activity. Investigators learned that several heads of poaching gangs in Mozambique were planning to take advantage of reduced ranger patrols and the lack of tourists in Kruger National Park.

The real problem was that – as lockdown disrupted earning ability and starvation threatened – bushmeat hunting began rising. In many poor countries, wild meat is a safety net suspended above destitution. People with nothing can always find something to eat or sell in the forest. This widened the types of species targeted and massively increased the setting of snares.

According to Andrew Campbell, CEO of the Game Rangers Association of Africa, ‘we can assume that bushmeat poaching is a result of the devasting economic impact the pandemic has had on livelihoods and that people are becoming desperate for food in these areas.’

Some African governments responded to the threat of zoonosis – a virus jumping from wild animals to humans – by banning the consumption and sale of all bushmeat (Malawi on 20 March) and bats and pangolins (Gabon on 3 April) in acknowledgment of the risks posed by hunting and poaching.

The Humane Society International office in Liberia said the Forestry Department intercepted a cargo of bushmeat, including the body parts of chimpanzees, monkeys, pangolins, and duikers. The meat was burnt on the spot in the presence of the local community to serve as a warning and a reminder that the trade of wildlife is an illegal and punishable activity. ‘It’s worth noting,’ it reported, ‘that not all bushmeat trade is for subsistence purposes and much is used for TCM (Traditional Chinese Medicine) and trade.’

With more than two million potentially hungry people on Kruger Park’s borders in South Africa, it’s hard to imagine the park will escape escalating bushmeat incursions. Late last year, park spokesman Ike Phaahla noted that bushmeat poaching was increasing, possibly driven by organized groups. Park rangers collected around 200 snares in one small area. This is unlikely to decrease at a time of rising hunger. A really serious threat is the collapse of long-haul tourism. This will also lead to a possible reduction of community rangers and overseas volunteers as hunting, tourist operations and donor groups hit hard times and began cutting back.

‘Conservation is going to face perilous conditions for the next few years,’ said Andrew Campbell of the Game Rangers Association of Africa, will be the collapse of long-haul tourism. This was confirmed by Charles Chari of the Bushlife Support Unit at Mana Pools in Zimbabwe. ‘Lack of tourism means massive funding cuts for many of our conservation and anti-poaching operations. ‘Because our resorts and lodges are empty, financial support for one of Zimbabwe’s most important sector is being drastically reduced. Empty safari camps are an indication of harder times still to come with an increase in uncontrolled poaching.’ The lack of tourists was also flagged as a poaching danger by Tim Davenport who directs species conservation programs for the Wildlife Conservation Society. ‘These animals are not just protected by rangers, they’re also protected by tourist presence,’ he told the New York Times. ‘If you’re a poacher, you’re not going to go to a place where there are lots of tourists, you’re going to go to a place where there are very few of them.’

‘I think COVID 19 has exposed a serious flaw in conservation strategy,’ said Botswana, ecologist Dr. Richard Fynn. ‘We have made the viability of conservation completely dependent on tourism/trophy hunting economics. Local people don’t benefit enough from conservation.’ It is clear that Covid-19 is changing the poaching landscape and increasing the dependence of poor communities on what they can hunt. Many countries have closed their national parks for now and tourism will probably flatline for the rest of the year. Hunger – and therefore bushmeat poaching – will be with communities for a long time.

For South Africa, the form that local and transnational crime will take depends on the type of state that emerges (survives really) after the pandemic. In some quarters there is hope that the shakeup caused by the pandemic could unblock impacted areas of planning, flush out poor leaders and crooks in the system, and lay the foundation for a cleaner, greener, and more robust state. Other predictions are that, with such high levels of poverty, food shortages, and widespread starvation plus a bleeding economy, mobs will overwhelm commercial suppliers of essential goods and raid farms and middle-class areas. This could lead to a transformation of South Africa’s constitutional democracy into a security-driven, authoritarian state. It could also result in poorer urban precincts ruled by warlords backed by feral, unemployed youth gangs into which police and army penetrate only in armored vehicles and clad in flack jackets. Of course variations of all of these scenarios are possible.

The international economy is taking a massive hit from Covid-19 and most countries will be thrown back on their own resources as trade and transport shallows and unemployment rises and tax revenue falls. South Africa under Jacob Zuma’s presidency was severely weakened and the ANC ruling party has not until recently displayed trustworthy leadership qualities that a post-Mandela population hoped for. How the new president, Cyril Ramaposa, handles the epidemic will be an indication of the quality of leadership that steers the country out of Covid-19’s morass. He’s doing quite well so far, but only time will tell. The population, confined to their houses, shanties, and hovels, awaits a post-pandemic country with rising anxiety.

PhD Don Pinnock